Thesis

The Barbary Pirates

Piracy and Diplomacy

Passports of Protection

The Barbary Wars

Significance

Tales From the High Seas

Process Paper and Annotated Bibliography

Courtesy of American Battlefield Trust

The United States negotiated with the other two Barbary States, Tripoli and Tunis, after the Algiers treaty was signed. These treaties cost the U.S a total of $160,000, as well as supplies and presents.

The American representative to Tunis, William Eaton, disliked the tribute system for the Barbary States. Eaton said, "there is no access to the permanent friendship of these states without paving the way with gold or cannonballs; and the proper question is which method is preferable.” (Constitutional Rights Foundation)

In 1801, Thomas Jefferson became president. Jefferson believed paying the pirates only led to more demands, announcing that no more tributes would be paid. In response, Tripoli’s ruler, the pasha, demanded that the U.S pay $225,000 on top of the annual tribute. Jefferson refused, and Tripoli declared war on the U.S.

In Jefferson’s First Annual Message to Congress, he announced “Tripoli, the least considerable of the Barbary States, had come forward with demands unfounded either in right or in compact, and had [threatened] war, on our failure to comply before a given day. The style of the demand admitted but one answer. I sent a small squadron of frigates into the Mediterranean. . . .” (Bill of Rights Institute)

Jefferson dispatched four warships to the Mediterranean. He did this without seeking a declaration of war, believing that a more decisive response was needed. He asked Congress for formal action. Congress then passed the “Act for Protection of Commerce and Seamen of the United States against the Tripolitan Corsairs.” (Bill of Rights Institute)

The act authorized an expanded force to “subdue, seize and make prize of all vessels, goods and effects, belonging to the Bey of Tripoli, or to his subjects.” (Bill of Rights Institute) Unfortunately, the squadron sent by Jefferson was unable to accomplish much.

In 1804 William Eaton began working to overthrow the Tripoli pasha, Yusuf Karamanli. He contacted Yusuf’s exiled brother, Hamet, promising he would have the U.S’s support in overthrowing his brother.

A new naval squadron led by Commodore Edward Preble blockaded Tripoli harbor in 1803. One of Preble’s warships, the USS Philadelphia, ran aground when it was pursuing a Tripoli ship. The pirates captured the vessel and crew. The pasha demanded the U.S pay $3,000,000 for peace and the release of their prisoners.

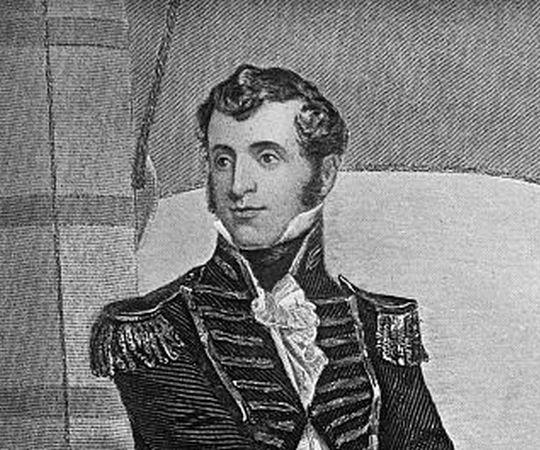

The Philadelphia was a frigate with thirty-six cannons. Preble knew the ship could not be left with the pirates, deciding to destroy it. Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and seventy others volunteered to attempt the dangerous mission.

Stephen Decatur - Courtesy of American Battlefield Trust

On February 16, 1804, under darkness, Decatur and his men sailed a captured Barbary ship into Tripoli harbor. They brought their ship up beside the Philadelphia and proceeded to light it ablaze. The Philadelphia exploded in the distance as they sailed away without casualties.

Months later, Commodore Preble gathered all of his warships and bombarded the harbor.

Plans of Tripoli Harbor - Library of Congress

In Egypt, Eaton and Hamet, with Arab mercenaries, eventually made it to Derna, a port town that was under the control of Pasha Yusuf.

Eaton and his men besieged the town on April 27, 1805.

Under the threat of U.S warships and Eaton’s army, Pasha Yusuf signed a treaty with the U.S. Yusuf agreed to release the prisoners from the American merchant ships and the Philadelphia.

The previous ruler of Algiers had been replaced with a man named Omar. Because of overdue tribute payments from the U.S, Omar captured several American merchant ships. In February of 1815, Congress authorized military action against Algiers. President Madison dispatched a squadron comprised of nine warships to end the Barbary tributes. This squadron was led by Decatur, who was now a Commodore.

Decatur captured several of Algiers’ pirate ships, before sailing straight into Algiers harbor on June 29, 1815. Threatened by Decatur’s warships, Omar quickly agreed to sign a peace treaty stating Algiers would never require the U.S to pay tribute again. Decatur sailed on to Tunis and Tripoli, with similar outcomes.